It is Tuesday 11th March. Today is the day. I wake up at 6am, have my last warm shower for a while and enjoy one last buffet breakfast at the hotel, before checking out and hitting the road. I get a twenty minute taxi to the outskirts of Santa Cruz, where I am met by my driver and two other new volunteers, Jorge and Jenny, whose English is about as good as my Spanish. I sit myself in the front seat and am overjoyed to discover that there is no seatbelt. The driver is fortunate enough to have one, but opts not to use it. We then proceed on a 45 minute car ride in which he spends more time on his phone than I do. I feel very safe. Later on, we pullover as he gets gas. This is not at a petrol station. I am very confused. After a short wait, he gets the car running by directly accessing the engine and we set off on the next five hours of driving. As we leave the city, we pass long queues of cars and motorbikes. At first, I think they are parked, before realising that there are drivers in all of them. The queues end at petrol stations. It turns out that Bolivia is going through something of a fuel crisis at present. Our driver, quite fortunately, clearly has contacts.

Over the next five hours, I enjoy a whistle stop tour of Bolivia, reminding myself of all the classic roadside sights. We pass Mennonites travelling along in their horse and carriages and stray dogs crossing the highway outside lines of stores. The driver continuously slows down to pass bumps and holes in the road and each time we hit a toll station, a group of women swarm in with the hope of selling us bread and Coca Cola. After four hours have passed, the road begins to look familiar as we drive through Guarayos, the local town we used to hitchhike to on Saturdays. The scenery isn’t very Amazonian yet. This is largely due to the amount of deforestation that has taken place over the decades. Farmers have been clearing land to grow crops and rear cattle. If the charity hadn’t bought the section of rainforest I am on my way to, it probably wouldn’t exist anymore.

In the last few minutes of the journey, trees begin to tower over the van and the heavens open. I see the sign for the park and we make a turn. Now it feels like the Amazon. I remember nine years ago, turning up on a bus in the middle of the night; the surroundings kept a mystery until I woke up the next morning. This time, it is all in plain sight. It feels different. More overgrown. With my arriving during working hours, I wasn’t expecting to be greeted by a line of smiling faces, but equally, I wasn’t prepared for the eerie sight of several masked figures stood outside the old Comedor as I entered. Everyone’s body is covered from head to toe and over each face hangs a mosquito hat. The crowd dissipates as everyone walks off to their afternoon work and I am ushered into the office by Jenn, the park coordinator, who I have been in contact with beforehand. We gather the bags from the car, pay the driver and then wait for Jenn, who has also just arrived and has things to sort out. We are then shown to our rooms and sort our beds out before beginning the formal introduction.

Before going any further, it is really worth getting into what the charity is all about. Bolivia has an illegal pet trade. The illegal pet trade is in fact the third biggest illegal trade worldwide, with many folks around the globe believing it is a good idea to get a monkey or a jaguar as a pet. These animals are wild and belong in the wild. All of the animals at the park have been rescued from homes of abuse. Originally, many were rescued from the circus and now, many of the animals in residence were the victims of poaching and illegal trafficking. Releasing them back into the wild is generally not an option. With most being separated from their mothers when they were young, they missed out on essential breastfeeding and thus have compromised immune systems. Furthermore, they were not taught to hunt and gather for themselves, and in some cases, do not know how to avoid predators. The greatest predator in the jungle is mankind and animals need to know to avoid human beings in order to survive. These animals have been humanised from a young age and thus lack this survival instinct. Rehabilitation is not easy to achieve and in the case of cats amounts to a 2% survival rate. The group of monkeys I worked with last time I visited the park have been semi-released, meaning that they are roaming free and fending for themselves, but stay close to the park where they are safe and where any humans around will not cause them harm. This could only be achieved once they were in a big enough group. The park provides a home to animals that have had any chance of living a life in the wild taken away from them by human hands. The enclosures the animals reside in are ginormous and full of jungle and the volunteers who feed and look after them also provide enrichment and company, as well as the opportunity to leave their home and explore more of the jungle if the circumstances are right. Emphasis is made early on that these animals are wild and that we are here to help them. They are not here for our entertainment. Photography is banned, except for long term volunteers, where appropriate and an understanding that these animals are in no way domestic, nor should they be made to partake in domesticated activities, is necessary in order to continue at the park.

I enter the office and I am greeted by Jenn, who welcomes me and invites me to watch a presentation outlining the purpose of the park and the history of the charity. We then go over some house rules and I make my payment for the weeks ahead. This is a modest fee that covers my food and accommodation whilst I am here, as well as the food for the cats. She also takes me on a tour of the park. Throughout this afternoon, I am somewhat taken aback by how much has changed. For starters, the living area itself is quite different. The accommodation is the same, as is the drop toilet at the end of camp. We do our business over a hole, sprinkle on some ash and place any toilet paper in a bucket to be burned the next morning. These fill up large bins that are then emptied into a poo hole by some willing volunteers every couple of months. The showers have also not changed, with the candle holders sticking out of the walls a relic indicating their age. The park has electricity now. It is limited, but the Comedor, where we eat and have the morning annuncios now has a light and an electric kettle. We used to dine by candle light. It was someone’s job each evening to ensure the candles were lit before dinner. The generator can no longer be heard roaring by the fridge. Instead, electricity from the road has reached the park and people are allowed to charge their mobile phones as often as needed. Now comes the biggest change. There’s phone reception. Moreover, the park has a WhatsApp group which is now used to exchange essential information. No more hunting each other down through camp to discuss things and no more coo-eeing loudly through the bushes to communicate with volunteers in the nearby forest. We can communicate anywhere. The camp animals have changed, with the birds moved elsewhere and Matt Damon, the iconic rhea, who used to join me for the last section of my walk back from seeing Ru the jaguar in the afternoon, now deceased, with his face living on in the group WhatsApp profile photo.

Having spent my afternoon reading a mountain of files on emergency protocols, animal enrichment and feline care, I head into the Comedor for dinner. I am met with a sea of faces, all unfamiliar. Where are Karen and Sampsa? Where’s Marta? Where is Dr Pete? I serve myself up some grub and find a group of people to join. When I was last here, at the adolescent age of 20, I was by far one of the youngest. This time around, I am certainly one of the oldest. I feel like the new kid at school as I find the confidence to get a conversation going with those around me and find myself a friendly group. After making my introductions to a small fraction of the team, I then take myself to bed to finish off reading before a tricky night’s sleep on the firm hay mattress.

The next morning, I am woken by the sound of a howler monkey in the distance. This is a comfort. The long gurgling roar is the centrepiece of the Amazonian soundscape for me. The howler monkey’s howl is known to travel for up to 7km through thick jungle. I remember my old morning routine from when I was last here. I would set off at 7am to feed the howlers, and Biton, the eldest, would hop on my shoulder as I entered his house and begin howling right in my ear, before dropping his breakfast down me. The sound is better enjoyed from a distance. What follows this morning is a series of alarm clocks chiming. Ah yes, we all have phones now. When I was last here, a man named Jonathon would pace up and down the park at 6am, singing with his guitar. This was our wake up call.

I get myself dressed and head to the Comador for breakfast and our morning announcements, or “annuncios”. Breakfast hasn’t changed – two pieces of bread. Nutritious. The team assembles and we get ourselves comfy in order to begin listening to what the new (or in fact very long term, at this point) leaders of the park, Jenn and Cleo have to say. This, as usual, includes general news and reminders, as well as introducing myself, Jorge and Jenny, who I arrived with yesterday. I am pleased that annuncios has maintained the same energy as it had nine years ago. Everyone then sets off to see their morning animals and I meet Cleo to discuss which animals I will be working with. This ends with my obtaining another pile of files to read. I start by taking these into the Fumador, a hut by the road, and the only place anyone is allowed to smoke. This used to be where we socialised in the evenings. My friends Hannah and Sam could always be found there, as well as Julia, Dr Pete and many other colourful characters. It was a safe place. Somewhere I could always go to find conversation. It was the only outside spot where we could sit in a circle and play card games and properly chat. The smoke also kept the mosquitos away. Now, it is quite empty. The hammock is sodden with rain water and even with Jenny and Jorge smoking next to me, the mosquitos still swarm in. There is nowhere safe outside during wet season. They are everywhere. I opt to read the second animal file in my bed, under the mosquito net. My room is a bit dingy and there is an odour due to the lines of clothes drying inside. It would only take an afternoon to dry all your washing when I last visited, during the dry season. Now, every clothes line is full, with frequent heavy showers meaning everything will always remain at least a little damp. I finish my reading and then head into lunch, before embarking on my first afternoon of work.

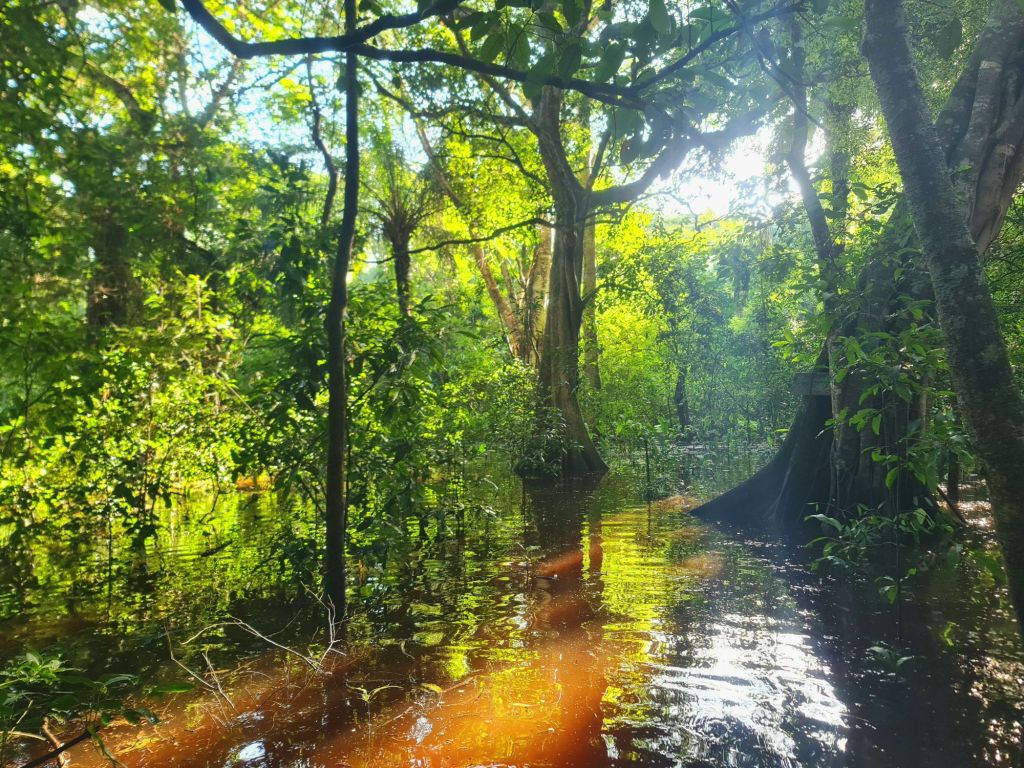

It is 2pm. This is when the afternoon shift starts. As I am waiting for my coworker, Marine, I collect the keys for the enclosure, fill up a water bottle for our animal and collect his bucket of meat from the fridge. I know the drill. Marine then joins me and takes me into the second hand clothes shop, Cochabamba, to find me a second hand mosquito hat. She says I will need it for where we are going. We then begin our walk into the jungle. Last time I was here, all of my animals were a ten minute walk away. Furthermore, the paths were dry and easy to navigate. Today’s walk is over half an hour. We have to navigate our way through overgrown bushes and several fallen trees. The ground is boggy and not before long, we reach a flooded region. Here, we trudge through the bog until the water reaches our knees and begins to flood our welly boots. I savour the last moment in which my feet are dry. We stumble along, trying to avoid tree trunks that protrude out of the hidden ground, before finally leaving the swamp again and emptying our shoes. We then walk for about ten more minutes before stopping just shy of the enclosure. At this point, as not to startle our feline friend on approach, we pause to let him know that we have arrived. “Hola, Kusiy”, we each shout.